The Sharp Decline in Violent Crime Can Be Attributed to

Each year, when the federal government releases new crime statistics, reporters seek out crime experts to assistance translate the numbers. But following three decades of climbing crime rates, the downwards trend of the past two decades has left fifty-fifty the experts searching for answers. Law-breaking dropped nether Democrats like Pecker Clinton and Barack Obama and when Republicans similar George Westward. Bush were in charge. Criminal offence dropped during times of peace and times of war, in the boom times of the late 1990s and in the Swell Recession era from 2007 to 2009. In recent years, both criminologists and the public have been baffled by the improving law-breaking state of affairs—especially when many other social indicators looked and then bleak.

But social scientists are starting to make sense of the big U.South. criminal offense drop. At least amongst many of the "street" crimes reported past law and victims, today's crime charge per unit is roughly half what information technology was just two decades ago. This isn't because people are twice as nice. Rather, the reasons behind the offense drop involve everything from an aging population to amend policing to the rising ubiquity of cell phones. At that place's no single "smoking gun" that tin business relationship for the drib: both formal social controls, such as police and prisons, and broader shifts in the population and economy play a role. That is, the main drivers are all social. Crime is less probable these days because of incremental changes in our social lives and interaction with others, including shifts in our institutions, technologies, and cultural practices. Earlier unpacking these social sources of the crime drib, we demand to look a little more closely at its timing and variation beyond offenses, from auto theft to murder.

Dropping Like a Rock

It might not experience every bit though the The states is appreciably safer, merely both violent and property crimes have dropped steadily and substantially for nearly xx years. Whether looking to "official" crime (reported to the police) or victimization surveys, the story is the same—both vehement and property crimes take dropped like a stone. While law-breaking rose throughout much of the 1960s and '70s, nigh of today'due south higher freshmen have not experienced a significant rise in the crime rate over the course of their lives.

For all the talk about crime rates (technically, the number of offenses divided by the number of people or households in a given place and time to adjust for population changes), we only have good information about trends for a limited set of offenses—street crimes like murder, rape, robbery, aggravated set on, burglary, theft, auto theft, and arson. Criminologists generally look to two sources of information to measure these crimes, the "official statistics" reported to the police and compiled as "Office I" offenses in the FBI's Uniform Offense Reports (UCR) and reports from crime victims in the big-calibration annual National Criminal offence Victimization Survey (NCVS). The official statistics are invaluable for understanding changes over time, considering the reports have been consistently collected from virtually every U.S. jurisdiction over several decades. The victimization data are also invaluable, because they aid account for the "nighttime figure" of criminal offense—offenses that get unreported to the police and are thus missing from the official statistics. Although both speak to the wellbeing of citizens and their sense of public safety, they practice not necessarily show u.s. the whole law-breaking moving picture (they omit, for case, nigh white-neckband crime and corporate malfeasance). All the same, when victimization information tell the aforementioned story as police statistics, criminologists are generally confident that the trend is real rather than a "blip" or a mirage.

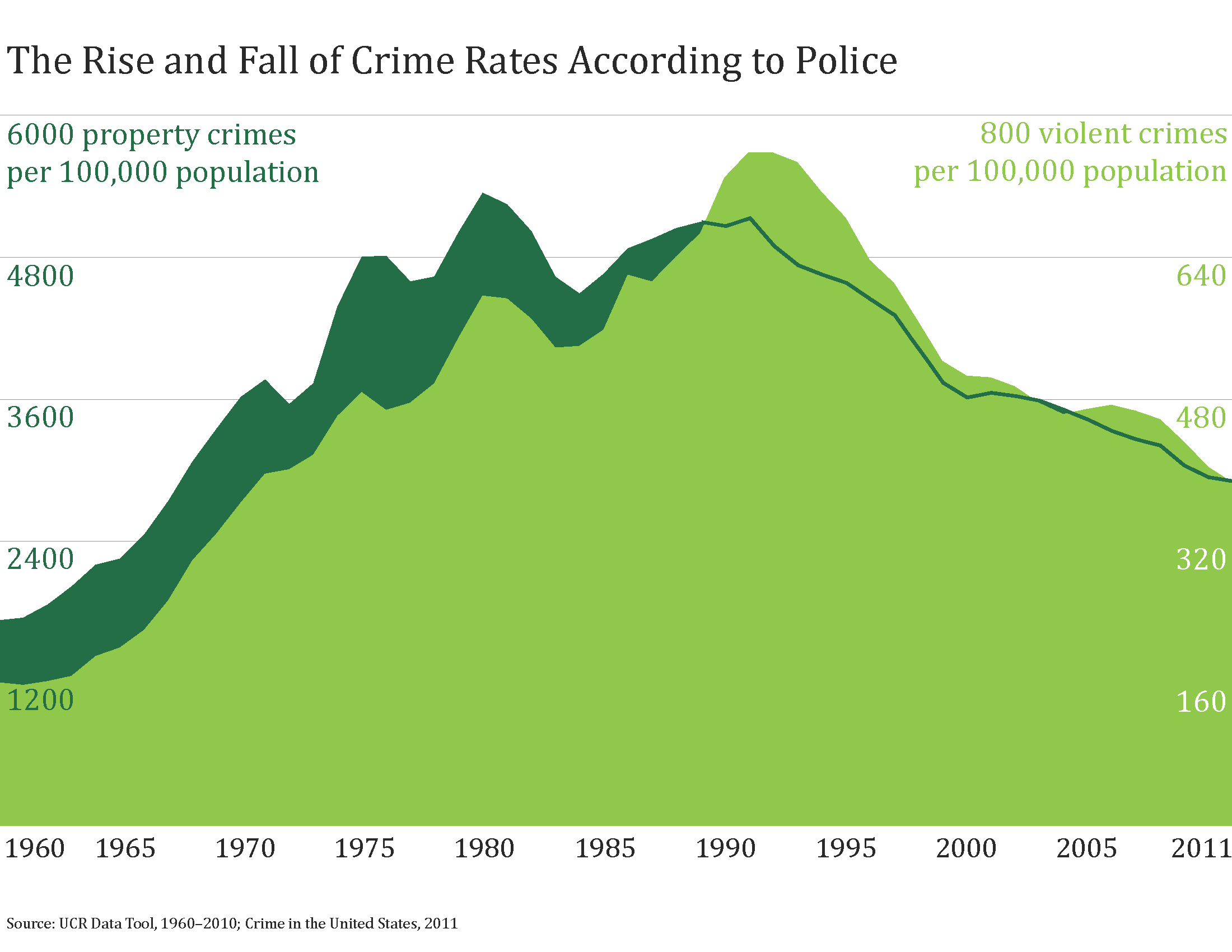

First, allow's look at the "Part I" law-breaking rate according to the official FBI statistics. Belongings crimes like break-in and theft are much more than mutual than violent crimes such as rape and robbery (equally shown by the larger numbers on the left axis relative to the correct axis). Both were conspicuously rise from the 1960s to virtually 1980. After some fluctuation in the 1970s and '80s, both rates of reported violence and property crime cruel precipitously in 1991. Since and then, official statistics show drops of about 49% and 43%, respectively. The sustained drop-off looks even more remarkable when compared to the earlier climb. Official 2011 statistics bear witness offense rates on par with levels last seen in the 1960s for property crimes and in the early '70s for fierce crime.

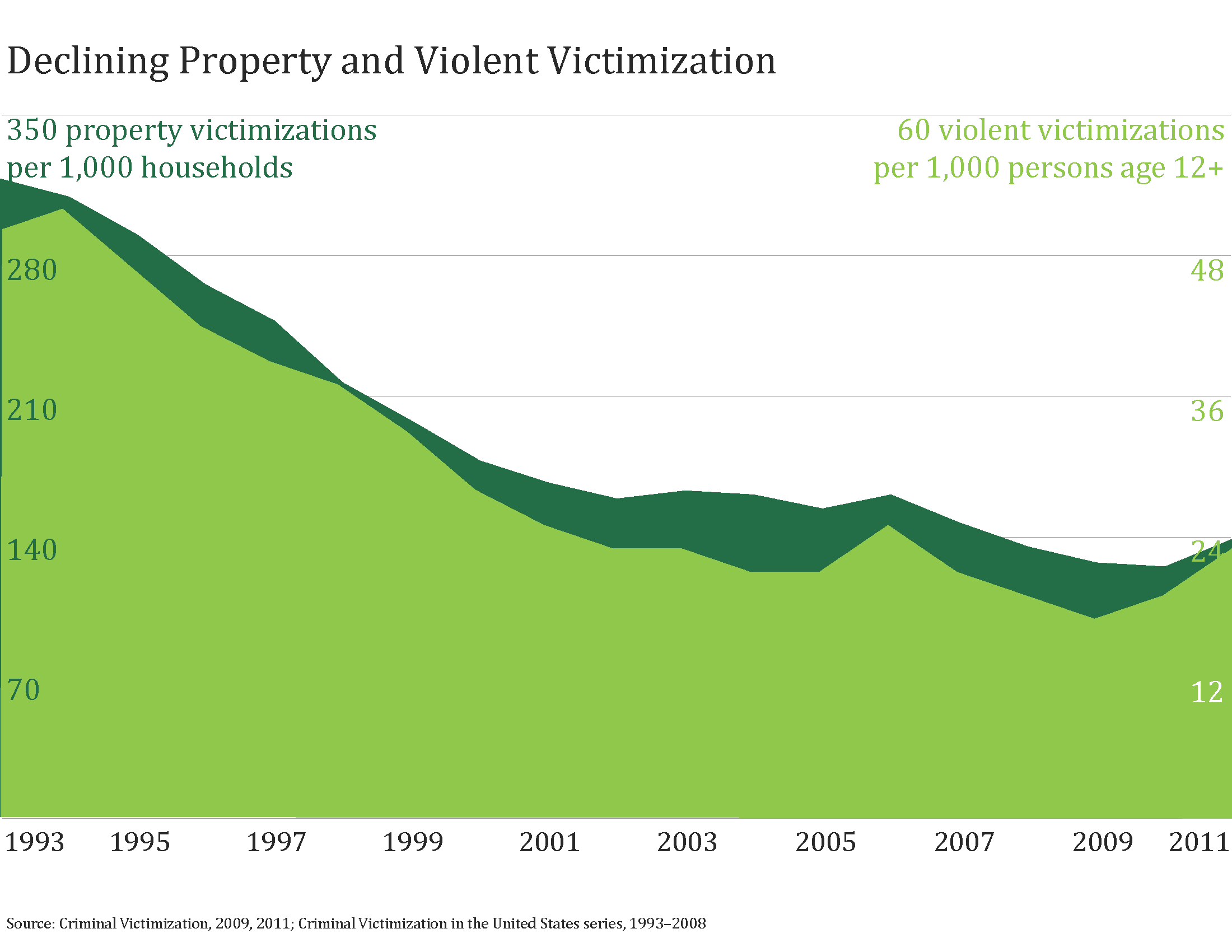

The federal government began taking victimization surveys from a nationally representative sample of households in the 1970s. The victimization film is clouded by recall errors and other survey methodology challenges, simply it'due south less distorted by unreported crime than the official statistics. Because the survey was re-designed in 1992, nosotros bear witness simply the trend in property and violent victimizations from 1993 onward.

Like the official statistics, the victimization data likewise testify a broad-based and long-term crime decline, though there is some evidence of a slight uptick past 2011. There is a drop in violent victimizations through 2009 and a drop in belongings victimizations through 2010 (autonomously from a slight rise in 2006 that followed a alter in survey methodology). Over this time, violent victimizations fell by 55% (from approximately 50 per one,000 persons age 12 or older in 1993 to 23 per i,000 in 2011). Holding crimes vicious by 57% (from 319 per i,000 households in 1993 to 139 per i,000 households in 2011). In both cases, the victim data suggest that the criminal offence drop may exist even larger than that suggested by the official statistics.

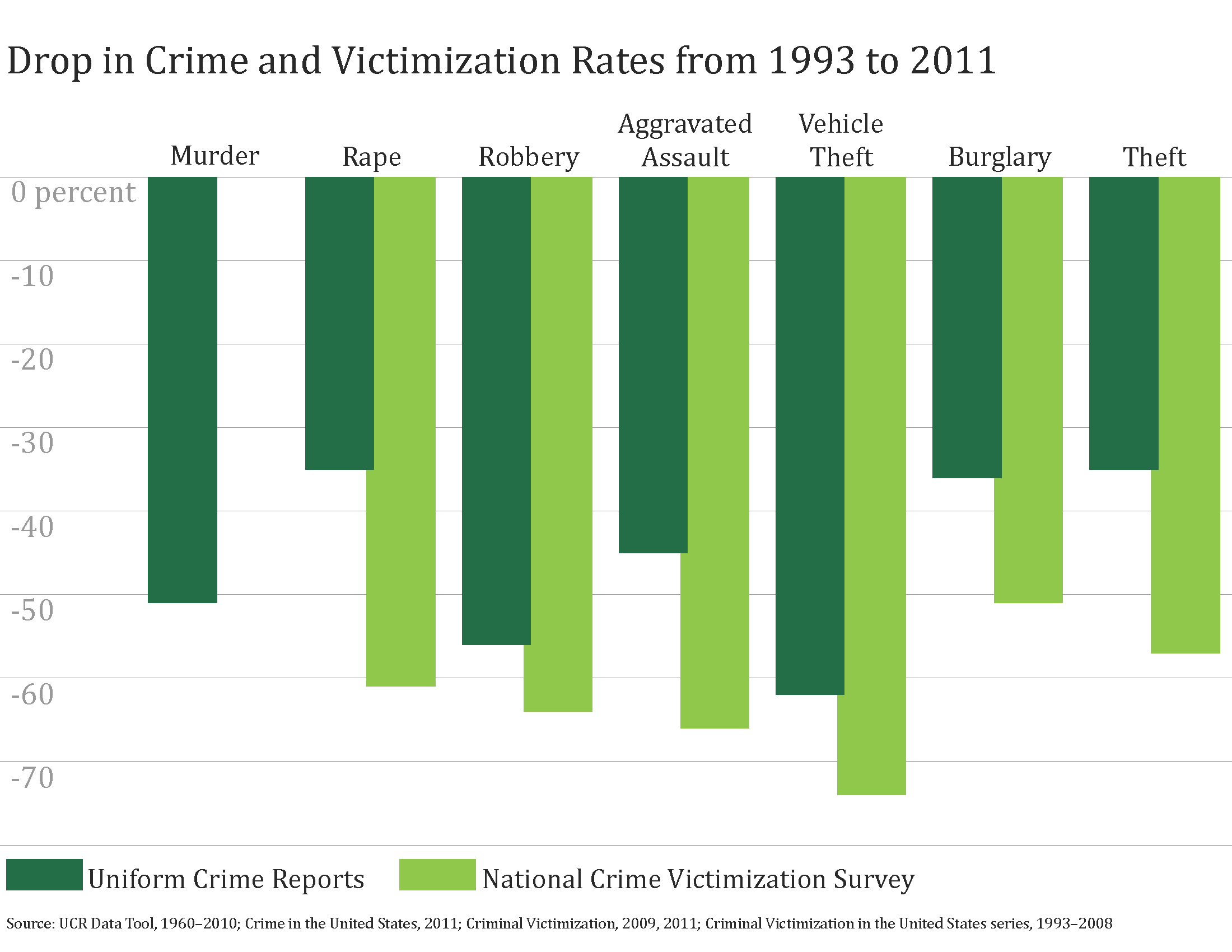

Information technology isn't only one blazon of offense that vicious. All seven of the "Part I" offenses reported in the constabulary statistics and the closest corresponding victimization offenses declined by at least 35% from 1993 to 2011. Although the specific offense categories are not straight comparable, similar types of crimes dropped in both the official statistics and the victimization data. For example, the steepest drops occurred for motor vehicle theft, which fell by 62% in official statistics and 74% in the victimization information. Taken together, this provides firm evidence that the crime drop is real, long-lasting, and broad in scope.

Six Social Sources

The large crime drop implies that either fewer people are participating in criminal offence or that those who exercise participate are committing crime less oft. Only a order'due south charge per unit of crime is not a simple aggregation of the number of "criminal offence-prone" individuals with particular psychological or biological characteristics. Under the right or, more precisely, the wrong social conditions, we are all prone to commit criminal acts. Communities therefore attempt to organize social life in ways that make crime less likely. While nosotros frequently acquaintance offense with institutions such as the police or courts, anything that alters patterns of human interaction tin can drive the crime rate up or down. This includes the technology in our cars, the places nosotros go for amusement, and the medical advances affecting reproduction and crumbling.

The idea that crime is social rather than individual is a prominent theme in much of the best new research. The crime drop partly reflects the work of institutions that are explicitly designed to increase social control, just it also reflects changes in other institutions designed to perform different societal functions.

Scholars have notwithstanding to neatly partition the unique contribution of the 6 social sources of the criminal offence drib, merely we can summarize current thinking about their likely touch on.

Formal Social Control and Criminal Opportunities

- Penalization. No discussion of contempo U.Southward. law-breaking trends would be consummate without considering our nation'south prison population, which increased from 241,000 in 1975 to 773,000 in 1990 to over i.6 1000000 in 2010. Because incarceration rose so rapidly, it is tempting to attribute the lion'due south share of the offense driblet to the incapacitating furnishings of prison. But if this were the case, as law professor Franklin Zimring points out, nosotros should have seen an earlier crime drop (when incarceration offset boomed in the 1970s). Instead, since offense is closely tied to the demography of the life course, new cohorts of potential offenders are always replacing those removed via incarceration. Moreover, many criminologists believe that prisons are actually criminogenicin the long-run, strengthening criminal ties and disrupting non-criminal opportunities when inmates are released.PunishmentIn one of the most sophisticated studies of the effect of imprisonment on criminal offense, sociologist Bruce Western estimates that roughly nine-tenths of the law-breaking drop during the 1990s would have occurred without any changes in imprisonment. Economist Steven Levitt attributes up to one-tertiary of the total refuse to incarceration. Ascension rates of imprisonment thus business relationship for at least some of the crime drop in the 1990s and 2000s, with scholars attributing anywhere from x to 30% of the refuse to America'due south incarceration boom.

- Policing. Both public and private policing strategies have inverse considerably over the past several decades, as have the technologies bachelor to law enforcement. Zimring and others conclude that "cops matter," particularly in explaining New York City'southward crime refuse. More than specifically, criminologists David Weisburd and Cody Telep identify targeted policing of loftier-crime "hot spots," gun crimes, and high-rate offenders, besides every bit proactive problem-oriented policing and the apply of DNA evidence every bit police practices that reduce crime. In dissimilarity, they find little evidence for the effectiveness of policing tactics like random preventive patrol, follow-up visits in domestic violence cases, and Drug Abuse Resistance Didactics (the DARE program).PolicingWhile Levitt is skeptical most the role of new policing strategies, he attributes a portion of the 1990s crime driblet to increases in the number of officers on the street. Considering of the criminogenic furnishings of prison house, scholars such as economist Steven Durlauf and criminologist Daniel Nagin propose shifting a greater share of criminal justice funding in policing. Constructive constabulary enforcement is part of the film, says criminologist John MacDonald, merely he also argues that public-private security partnerships such as targeted "business improvement districts" have helped to sustain the pass up. The unique contribution of policing to the current law-breaking drop is probable meaning, just limited—bookkeeping for mayhap ten to xx% of the overall decline. Moreover, the effectiveness of the formal social controls provided by police depends, in large function, on back up from informal social controls provided by families and communities.

- Opportunities. Apart from changes in prisons and policing, the opportunitiesfor crime accept changed rapidly and dramatically since the 1990s. Technology isn't an obvious social source of the crime drop, just people have been connecting in fundamentally unlike ways in the past ii decades, altering the risks and rewards of criminal behavior. When information technology comes to "target hardening" (crime prevention through environmental design), simple changes can brand an enormous departure. Remember that the biggest drop amongst all criminal offence categories was in auto theft—in the U.s.a. and around the world, new technologies like car immobilizers, alarms, and central locking and tracking devices have effectively reduced this crime.OpportunitiesMore generally, surveillance provides guardianship over ourselves and our holding. Information technology may fifty-fifty deter others from acting against u.s.. With regard to a now-common engineering science, economists Jonathan Klick and Thomas Stratmann and criminologist John MacDonald point to the amazing proliferation of prison cell phones. They argue that cells increment surveillance and a would-be offender's risk of anticipation, which affects the perceived costs of offense. Many potential victims now have easy access to a camera and are within a few finger-swipes of a phone call to 9-1-1. In a follow-up interview with the authors about his research, MacDonald said that the crime drop is "driven in part by target hardening, in function by consumer technological shifts, and in part by the move of people's nighttime activities dorsum to the house." In sum, where we spend our time and who is watching u.s.a. probable plays a big part in the recent criminal offence pass up.Of grade, efforts to constrain criminal opportunities can as well constrain non-criminal activities—and while near of us welcome the declining criminal offense rates that accompany greater surveillance, we are far more ambivalent about being watched ourselves. As criminologist Eric Baumer explained to the authors, "not but are we spending more time off the streets and on a computer, but we are being watched or otherwise connected to some form of 'social control' pretty constantly when we are out and about." Information technology is difficult to quantify how myriad small changes in criminal opportunities affected the criminal offence drop, but their combined contribution may be on a par with that of formal policing or prisons.

Social Trends and Institutional Change

- Economics. More than ninety% of the "Part I" crimes reported to the police involve some kind of financial proceeds. The human relationship betwixt crime and the economy is more complicated than the unproblematic idea that people "plough to crime" when times are tough, though. Opposite to popular expectations, for example, both victimizations and official crime showed especially steep declines from 2007 to 2009, when unemployment rates soared. Robbery, burglary, and household theft victimizations had been falling by a rate of almost four% per year from 1993-2006, but savage past an average of half-dozen to 7% per year during the Great Recession.Economic scienceThis is non because crime is unrelated to economic conditions, but because criminal offence is related to then many other things. For example, when people take less disposable income, they may spend more time in the relative rubber of their home and less time in riskier places like bars. As noted above regarding opportunities, another reason crime rates are likely to drop when greenbacks-strapped residents stay home at nighttime in front of a television or computer screen is that their mere presence can help forestall burglary and theft.Criminologists Richard Rosenfeld and Robert Fornango suggest that consumer confidence and the perception of economical hardship may account for as much as one-third of the recent reduction in robbery and belongings crime. Nevertheless, while economic recessions and consumer sentiment are likely to play some office, they cannot account for the long and steady declines shown in the charts to a higher place—blast or bust, offense rates accept been dropping for twenty years. For this reason, most criminologists attribute only a small share of the crime drib to economic conditions.

- Demography. Law-breaking, information technology seems, is largely a immature human's game. For most offenses, crime and arrests peak in the tardily teen years and early on twenties, declining quickly thereafter. During the 1960s and 1970s, the large number of teens and immature adults in the Infant Boom cohort drove crime rates college. In societies that are growing older, such as the contemporary United States, there are simply fewer of the young men who make upwardly the majority of criminal offenders and victims. Due to these life course processes, the historic period and gender composition of a society is an underlying cistron that structures its charge per unit of crime.DemographyAn influx of new immigrants might also exist contributing to lower offense rates. Co-ordinate to research by sociologist Robert Sampson and his colleagues, immigration tin can be "protective" against crime, with first-generation immigrants beingness significantly less likely to commit violence than 3rd-generation Americans, later adjusting for personal and neighborhood characteristics.While criminologists approximate that demographic changes can account for perhaps 10% of the recent crime drop, these factors are changing besides slowly to explicate why criminal offence was essentially halved within the course of a single generation.

- Longer-term Social Dynamics.Drawing back the historical drape on U.Southward. crime rates puts the contempo drop in perspective. So argued historian Eric Monkkonen, who showed that the urban homicide rates of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were on a par with the "peak" rates observed in the early on 1990s. In fact, historical evidence amassed past scholars including psychologist Steven Pinker and historical criminologist Manuel Eisner convincingly shows that personal violent crime began declining in Western nations equally early on every bit the sixteenth century. While this research has emphasized violent crimes, similar processes may hold for crime more generally. Perhaps the rising offense rate from World War 2 through the early 1990s was just a small spike that temporarily obscured a much longer downward trend.Social DynamicsThis long historical sweep may offer little solace to those confronted by crime today, simply the encouraging long-term trend suggests explanations with deep roots. Eisner points to subtle shifts in parenting occurring over a long time span; Pinker suggests greater interdependence and broadened circles of people with whom we tin empathize. Both draw on classic sociological piece of work by Emile Durkheim and Norbert Elias, who attributed historical changes in criminal offence and social disorder to changes in the relation between individuals and gild. The centuries-long crime story is mayhap best explained past the gradual development of formal and breezy social controls on our behavior. In this light, Baumer argues that nosotros should at least think more expansively about the contemporary crime driblet. We cannot say for certain where the crime charge per unit will be in five years, but if we had to bet where the crime rate would be in 1 hundred years, nosotros could be reasonably confident information technology'd exist measurably lower than it is today.

Room for Improvement

Criminologists almost universally acknowledge a sizeable crime drop over the final 20 years. This does not mean that everyone'due south neighborhood became safer or that crime in the United States is low relative to other industrialized nations. In fact, U.S. homicide rates are more double those of Canada, Nihon, and much of Europe. Still, the U.Due south. offense movie has improved markedly, with significant beyond-the-board drops in violent and holding offenses. Moreover, as Baumer points out, even behaviors like drinking, drug apply, and risky sex are failing, especially among young people.

We cannot explain such a sharp decline without reference to the social institutions, weather, and practices shaping crime and its command. In detail, social scientists point to punishment, policing, opportunities, economics, census, and history, though at that place is fiddling consensus about the relative contribution of each. Further disentangling each factor's unique contribution is a worthy endeavor, but it should not obscure a fundamental betoken: information technology is their entanglement in our social globe that reduces crime.

Recommended Reading

Eric P. Baumer and Kevin Wolff. Forthcoming. "Evaluating the Contemporary Law-breaking Drop(s) in America, New York City, and Many Other Places,"Justice Quarterly. An upwards-to-the-minute appraisal of explanations for local, national, and global criminal offense trends.

Manuel Eisner. 2003. "Long-Term Historical Trends in Fierce Offense," Criminal offence and Justice. A rich treatment of the decline in European homicide rates from the 16th to xxth centuries.

Steven D. Levitt. 2004. "Understanding Why Law-breaking Fell in the 1990s: Four Factors that Explain the Decline and Half-dozen that Practice Non," Journal of Economic Perspectives. A systematic appraisement of explanations for the crime decline by the renowned economist and Freakonomics author.

Eric H. Monkkonen. 2002. "Homicide in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago," The Periodical of Criminal Law and Criminology. A careful historical examination of homicide in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Franklin Due east. Zimring. 2007. The Great American Crime Turn down. A well-written and thoroughgoing account of the U.Due south. criminal offence driblet.

Source: https://thesocietypages.org/papers/crime-drop/

0 Response to "The Sharp Decline in Violent Crime Can Be Attributed to"

Post a Comment